14-Day Beginner Series - Essential Composition

Mackenzie SwensonHi, I'm Mackenzie Swenson, and welcome to the fourth day of our 14-day beginner series. Today, we're gonna be talking about essential composition. And I've broken down what is a very big, expansive topic that many, many books have been written on, and many people have tried to understand over the years. And so this is gonna be just a brief kind of overview of a few things you can think about when you're trying to compose a painting or drawing, or even a lens to look at the images that you're drawn to, and start to understand what are the things that tie those images together? What are the things that are kind of understandable tidbits that are a common denominator between all of the paintings and drawings that I like.

So, the first thing that we're gonna talk about is what I like to call composition tools. And tools is maybe a little bit of a strange word to use for this, but the reason I say tools is because they're going to be these very specific concrete components that are present in almost every drawing and painting, that you're going to be able to use when you start to craft and create your own work. And so those compositional tools are drawing, value, and color. So after we talk a little bit about that, we're gonna get into design, and design has to do with how things are placed within a frame. And so a little bit about, you know, composing the dimensions or the aspect ratio of, or I guess it's just the ratio of like height to width of what you're creating, and how to place things within that.

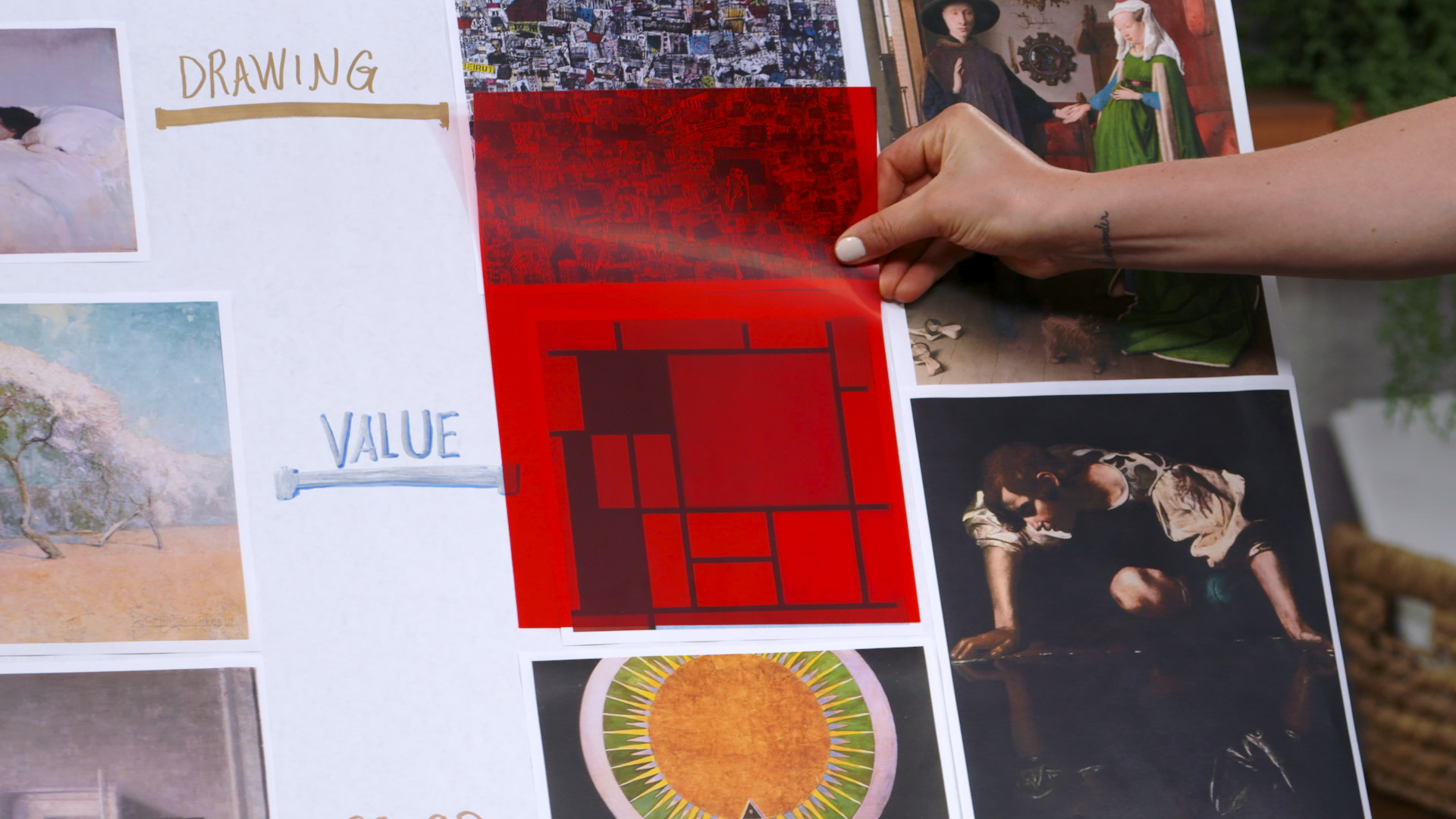

And then the last thing that we're gonna talk about is balance, what to pay attention to to make sure you have a balanced composition. The very first thing we're gonna talk about is drawing. And if you look over here, what you'll see is I've got this kind of collage-like looking series of a number of some more famous and some less famous paintings. And what we're gonna focus on for drawing is just this top line of images here, these four pieces. And so over on the far left, just so you guys know what it is that we're looking at, we have this beautiful landscape by a painter named David Grossman.

And then here we have a painting called Madre by Joaquin Sorolla, who was a painter in the late 1800s, early 1900s, contemporary of like John Singer Sargeant. And that is a more modern expressionistic example, and then a more classical example of paintings that exist on the simplicity side of drawing. So for the purposes of this, I'm identifying drawing as the number of individual objects and boundaries placed within a painting or drawing. So the reason that these two would be identified as simple drawing is because if you look at this painting here, sorry, the David Grossman painting, you could break it down really into just almost two shapes, right? And maybe there's this little guy here, but like it's very, very simple.

It's more characterized by broad expanses of color, big shapes. And the same, even though this is, I mean, they're both somewhat representational, right? It's a landscape, and then this is a, you know, a dual portrait, an interior. But again, there's this line really in the middle, identifying the wall and the bed, and then you have, you know, the mother's head, which is all kind of condensed there. It's not too detailed, it's pretty simplified, and then the infant here.

And so these are both examples of the simple side of the drawing spectrum. So then on the other side of the drawing spectrum, we have a modern example, so this is an artist named Zena Assi. This is one of her paintings called war, or I'm sorry, Art, War, and Beirut. And then this is a painting by a man named Jan van Eyck, and it's called the Arnolfini Wedding. So it's, I believe it was the 1500s.

And so if you look at this side, this, I would say, is complex drawing, right? For both of these. This one there's, you know, I mean, countless boundaries, individual things, little, you know, singular items happening inside this, right? And then over here, even though it's all recognizable objects, same thing, lots of complex detail oriented drawing, and individual items here. So even within, you know, the little portraits there's like, you could zoom into each little, you know, square inch of this painting, and it would be remarkably complex with the amount of drawing detail.

So if you're thinking about composition and drawing within composition, this is the range that you're kind of working with. On the far side, we have simplicity. So over on the left, and on this side, we have complexity, right? So then, if we move down to value, our second drawing tool, or I guess composition tool, we have on this left end of the spectrum, we have this, it's like untitled from 1961, I think, but this painting by Rothko. And then we have this painting here, by a painter named Emil Carlsen, called The Cherry Tree.

And so these are both examples of kind of a mid tone, a mid tone focus for how the values are structured. So just to say a little bit about what value is, value is just how light or dark something is. So if we have this range of values, this is white to black, this is what I can achieve with oil paints. And typically I identify black as zero, and white as 10, just as a simple way of having an understandable range. So what we've got going on on this far left side here, is paintings that exist much more in the center, right?

They don't go into the extremes on either side. So they're very simple in that way. So they're kind of mid tone or tonalist paintings, and one easy way of identifying the values in a painting, or in something you're looking at, 'cause it can be hard when you've got color to really know where on the gray scale it is, something I do frequently is I'll actually take a photo, and then flip it to black and white. So that's one option. But another trick is actually to get a piece of red transparency, which unifies all of the colors, and what you end up seeing is just a darker and a lighter.

You just see the values really coming through. And so, you know, on again on this side, we've got a painting or two paintings that have that mid tone range as their focus. And then on this end of the spectrum, right, we have high contrast. So here we have a Mondrian painting, which one is it? It is called, oh, he's called it Composition with a Large Red Plane, and Red and Blue and Yellow, or something like that.

But it's a Mondrian painting that very much represents a high contrast image, even though it's very abstract. And then here, you have this Caravaggio painting of Narcissus, and this is also a representation of a very high contrast image. And so, you know, whereas here, you have paintings that are kind of existing in this center of the spectrum, without too much deviation onto the extremes, here, you have almost the opposite, where most of both of these paintings exists either in this range here, right? Or in this range here, and same with this Mondrian painting. Right?

And that's not to say, obviously nothing, it's highly unlikely that anything is going to be fully, you know, here, like to get something fully on this side of the spectrum, you just have basically a painting that's half black, half white, you know? And the most extreme version of this would be a painting that's literally just gray. So any work of art really does not exist on the defined, you know, end of the spectrum, but this helps kind of see what that range you can play with is. So then, just to kind of see here, what happens, you can see there's a tiny bit of the color that comes through, but it really simplifies it into just reading how dark, or how light something is. So if you do that, it does knock the values down a little bit, so they look, you know, some of these here then look more mid tone, but you can still see the contrast for sure.

You know, we've got these, and then some of those brighter values, and then over here, you can see all of that. It's not that it has no contrast in it, but it's really existing more within the center. And then definitely this Rothko, like he barely gets out of just one of these little values here. So again, the range that we're playing with there is a more mid tone painting, versus a high contrast painting. So then the last composition tool we're gonna be discussing is color, and color is a vast, mysterious thing that we're still learning about.

We still have, you know, so many unanswered questions about the nature of color, the emotional qualities of color, like all kinds of things. But one simple way to think about color here is over here, we have two paintings that are very neutral. So when I say neutral, I just mean it's like, if you are editing a photograph, and you move that saturation really, really far in the direction toward black and white, but not quite, I mean, it could be black and white, but basically it's just a very, very low saturation. And so you can see over here, this is an untitled painting by Hannelore Baron, an artist, I believe in the '60s, this was created, maybe the '70s. And so, you know, you don't have, like, I could identify this as a very, very low saturation version of yellow, right?

I could identify this little piece as a very low saturated version of red, but it's, you know, it's like, if you dropped a tiny bit of red in with like a brown, or a tan bucket of paint, right? Like it's tipped a little bit toward red, but it's not, it's not high saturation or it's not highly chromatic. So that's a more modern example. And then here, you have a painter named Vilhelm Hammershoi, and this is another example of a very neutral painting. So I mean, it's all, it's maybe a little bit toward blues, and a little bit toward blues, but really it's all kind of slight variations of grays and whites.

And so that's our kind of neutral side of the spectrum, and then on this side, we have, what we would say is highly saturated or highly chromatic. So you can think about like the most extreme version of a highly saturated color or a chromatic color would be like a neon sign, right? Like that's so far out on the spectrum of saturated, it's a very densely packed pigment. And so your eye registers it as being extremely bright. So on this side of the spectrum, we have images that use high saturation or high chroma.

And so this is a Hilma af Klint painting untitled number one. So you can see she's really playing up those bright greens, those bright reds, those bright yellows, blues, you know, I guess gold is kind of a color. It's actually not the most chromatic color. It's like in between an orange and yellow, but regardless, this painting definitely highlights a very chromatic or saturated use of color. And then here we have the 18th century, 17th century painter Fragonard, and this title of this painting is just The Swing, but he was a French painter, and he really played up chroma, and color, and saturation as well.

So you can see some of these really intense pinks, some of these really intense, bright greens, blues, like it's like someone really turned up the saturation on his paintings. So again, neutral to chromatic is the spectrum we're playing with, with color. And so what I like to think about, when I'm composing a painting is it's as though everything over here on the left represents a sense of calm, represents a sense of kind of the yin element, right? It's the, like, you can look at it, and you can just like breathe a little easier. Your heart rate goes down.

It's very, you know, we could call it low, it's a low energy, it's very relaxing. And then everything over here on the right has a lot more intensity. It's got this like kind of frenetic energy. It's the yang, it's the, you know, that side of the spectrum, right? So within a sense of polarity, like that's what we're playing with here.

And what I have found is that you do not want to have an image that you're making, where all three of these drawing, value, and color, are all pumped all the way up, right? Where you've got a lot of craziness happening, where you've also got a lot of high value contrast, and then you've also got a lot of crazy colors, right? That just ends up looking garish. It just ends up looking kind of amateurish. And like, you just, it's like the chef who throws all of the ingredients in, and it just tastes confusing.

And so it's an option. I'm sure there's an artist out there who's done that effectively, but what I like to think about is essentially having, okay. I don't know why I made that a capital L, I just did. But we've got drawing, value, and color, right? And then we have simple and complex.

We have mid tone, and we have high contrast, and then we have neutral, and we have chromatic. And let's, you know, get kind of fun here, and we'll say, we'll use this nice blue, kind of calm color over here. Right, and then we'll say over here, this kind of fiery orange, we're just gonna put a one. So between zero and one. Between, right.

So high fiery energy, low watery energy. So you don't wanna be all over here, but you also don't wanna be all over here. What you wanna aim for is to focus on one or two of these. It doesn't matter which one, it could be drawing and color. It could be value and color.

It could be drawing and value, like Caravaggio, like, you know, whatever one it is, and then you, or just value could be the thing you're focusing on, right? But the point being, you want to play with how you're mixing these scales. So let's say you have a really intense, complex drawing, then maybe you wanna keep your values, not totally mid tone, but maybe they're, you know, somewhere in here. And then you decide you're gonna have mostly neutral color, but with like a few really fun chromatic pops, right? That'd be a nice composition, in terms of balancing each of these tools, right?

So again, you wanna avoid this. We don't, I mean, if you wanna try it, you can, but good luck, but you wanna avoid this. You also are probably, I mean, I've actually seen this work more frequently than this, but this is also a very challenging composition to pull off. And then, you know, likewise, a lot of times you'll find like really boring compositions also happen when these are all in the middle. And so, you know, what I would say is identify what paintings, you know, like identify what you notice about how the paintings you like play with each of these three constituent elements, and then use that to kind of dictate how you start to play with them in your own paintings and drawings.

And I'm actually gonna have a little printout that you can use, that Is going to give you, you know, each of these individual things. So it'll show up like this, but you know, a little nicer, but the prompt for today is to take three paintings that you love. It could be abstract, it could be portraits. It could be, you know, like anything you want, and go through and just do your best to assess, you know, with each of those tools, where it falls on the spectrum, and see how those images mix those three different tools. And so, you know, you can just use like a marker or something and identify where you think the painting that you're doing is.

So if I were to, let's say, look at this image here, the Art, War, and Beirut, and I were to assess how it lands on the drawing spectrum. I would put that way up here. Right? And then if I think about value, it's definitely not as contrasty as this Mondrian, but it's definitely not as mid tone as like a Rothko. So I would put this maybe mid to high.

So I would put the value, and we could even throw this guy up, and see like, yeah, so there's a lot going on, but it doesn't hit the extremes everywhere. There's a lot of gray happening in that. So we would put the value probably around here, and then color with this particular painting. There are a few little pops of color, but it's really largely, very neutral, even, I mean, so we've got a really chromatic red right there, but it's the, really, the only one. We've got a couple really chromatic yellows, but they're tiny little spaces.

So I would say for color, this exists probably down here, more toward neutral. So that's the mixing board for this painting. So, you know, just pick a couple paintings you like, print off the handout, and see what you find. And, you know, let that kind of dictate some of the things you explore in your own, in composing your own pieces. So that is composition tools.

And then I'm just gonna very briefly talk a little bit about design, which is how you place objects within an image. And so there's really two, the two simplest and maybe most common things that people use for design. The first is called the rule of thirds. And so if I tape this up, it's a little transparency here. These are very useful, but let's say I put this here.

Oh, which one do we wanna do? The Caravaggio is kind of fun. So there, we've got, you know, approximately this image broken into thirds, both vertically and horizontally, and you can see, you know, not so much this bottom third, but definitely with this top one, his whole mass of his body is aligned right on that top third. And you've got where the arm and the shirt gets separated. The arm, the shirt gets separated here, and his face is like, his chin, like this is very heavily concentrated on this point right here.

So, you know, and there's also a little bit of tension happening kind of in this area here, goes right through that. So, and then I guess this bottom third really is where, it's not really the ground line. So I guess he played around with this, but you can see it coming into play with this top one, for sure. So that's, you know, there are so many more things within design that you can explore, but that's a really good, simple one to get you started. You know, you've got the bars that come up on your phone, if you wanna, you know, just play around with looking at how the rule of thirds plays into compositions.

So another thing you can look at is what's called the golden ratio or the Fibonacci sequence. That's like the ratio that the Nautilus shell kind of adheres to. There's a little video called Donald Duck in Mathmagic Land. It's fantastic, from, I don't know the '80s, maybe. So if you wanna know a little bit more about that, it's an interesting resource.

And then the last thing I wanna talk about is just balance, and I keep that very simple. So within balance, I always just bring it back to something I call big form, small form. And big form is that, you know, broad strokes image, like the way the big picture is designed. So, you know, like if we were to look at this Emil Carlsen, you've got the big shape of the tree here, and you've got the big expanse of the field, and then the sky, right? Like that's big form.

That's those, what you notice across the room. And then small form is those little things. These textures in the fields, the little, you know, bits of play within how the tree is like the leaves, and the texture on the branches. Like, when you zoom in close, it's those little moments that keep your interest, and make you wanna get really close to the painting, and just keep exploring. So for balance, what I find is that big form can either fall into simple or generic.

And I believe that simplicity is an absolute, an absolutely like, something to strive after. And that is, you know, that's when like, things are iconic, things are graphic. They catch you from far off, like simplicity is extremely compelling. When something is generic, it's boring, it's, there's nothing about it that's really, you know, it's still organized into like big shapes, but maybe there's too much symmetry in all the wrong places or, you know, you've simplified someone's head shape to just being kind of a ball instead of capturing those big, simple, interesting plane shifts. So, when you're looking at how to balance your big forms, aiming for simplicity, and then with small forms, I separate it into nuance, right?

So something that's very like, well observed, you know, there's a care, and you're paying attention to those really tactile, small moments, highly nuanced. And what I try to avoid is things being too busy, or coming off as overly detailed, kind of fussy. And so when I see something that's nuanced, it holds my attention up close, and it surprises me. Whereas when something is detailed, or overly busy, usually is, it just, it's annoying. Like, I don't know how to explain it other than that.

And so for me, I just follow my response to that. Like, if it pulls me in, I'm like, oh, they captured it. They did really nice, nuanced, small form. And if I look at it and I'm just like, ugh, it's way too much, I'm like it got busy, it got overly detailed. And so, or like visual noise.

So again, like, making sure that your image has that big, iconic graphic impact, but then also has little moments where you really dig into those small forms, and give people something interesting to grab onto up close. So again, we've got, you know, these three compositional tools of drawing, value, and color, looking at how you mix those. And then we have design, which, you know, is how you place all of the different components within the frame of your painting or drawing. And then we've got this balance of big form and small form, and making sure that you have those coexisting in a very appealing way. So, hope you learned a little something, and you can maybe look at the paintings you love and adore with some interesting new lenses.

And I hope to see you tomorrow. Thank you so much for joining us for this fourth installment in the 14-day beginner series.

Was wondering about the hand-out you mentioned. Where can I find it?

Great class!

Sorry, but I get distracted and find myself paying attention to her playing with her hair; I think she's so calm that it almost puts me to sleep. On a scale from 0 to 10, I give it a 2.

This is fascinating.

Thank you!Very detailed and useful information.

Great lesson. I like the compositional tools. I will look at some of the paintings I like and try to understand what is appealing by using these tools.

Like the way you teach . So happy to understand composition tools . Thanks for sharing .

Love the lessons so far! I’ve been painting on and off as often find myself stuck, but your explanation of the essential tools was easy to grasp and has made it more clear to me where I want to go with my abstract and representational paintings. I have all these ideas in my head and excited to paint again! What a great place to start for any artist at any stage in their journey. Thank you so much Mackenzie!